Samuel Morse: The engineer who painted a masterpiece

When you hear about an engineer who painted a masterpiece, the first person who probably comes to mind is Leonardo da Vinci -- especially coming from me since I've written about Leonardo recently. However, this article isn't about da Vinci. It's about Samuel Morse.

Yes, that Samuel Morse. The one who invented both the telegraph and Morse code and forever changed the course of global communications.

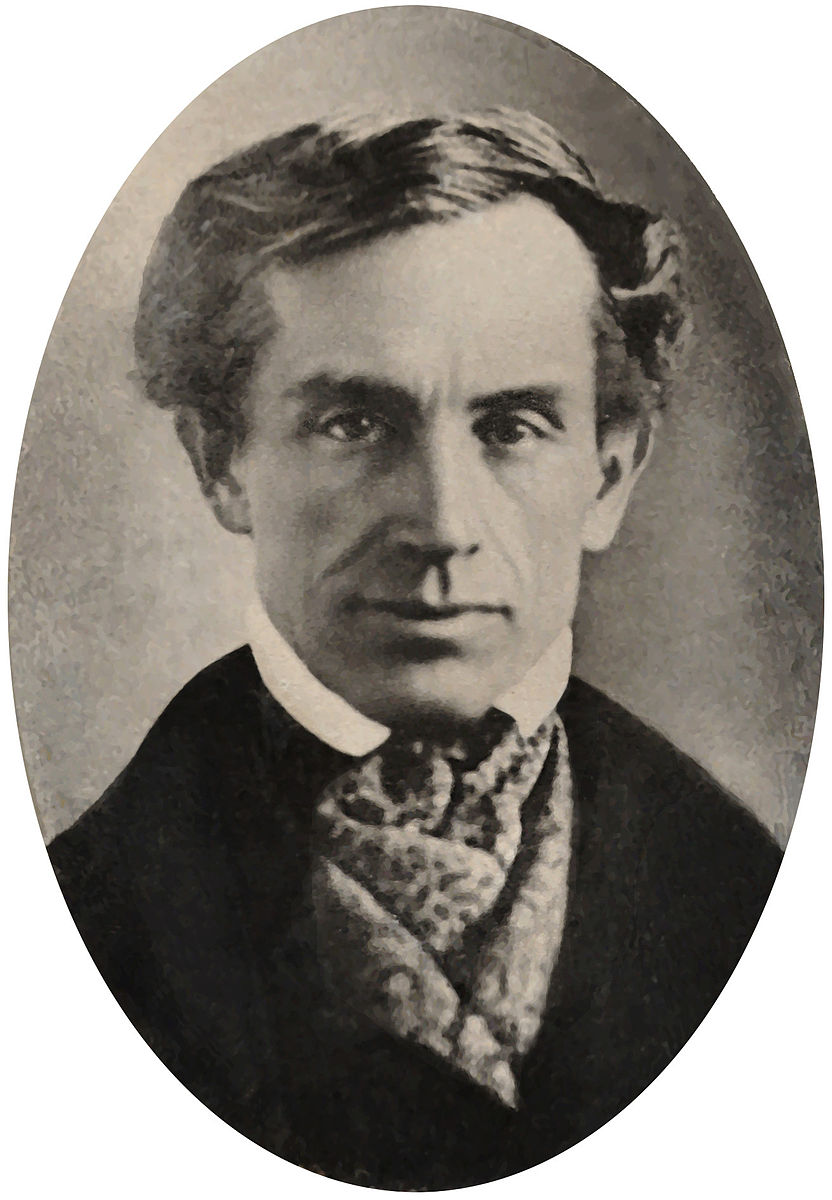

Most of the world has long since forgotten that before Morse (right) was an inventor, he was a painter. He was actually one of America's most prominent painters of the early 19th century. But, despite the fact that he painted the portraits of U.S. Presidents, military heroes, and many prominent Americans, what he really wanted to be was a "historical painter" in the mode of the great American artist John Trumbull.

During his lifetime Morse failed in that ambition, although he made a series of admirable attempts. That failure, however, opened the door for his eventual accomplishments as an engineer. However, one of Morse's attempts at historical painting has now gained the appreciation and acclaim of the public over a century after his death. That painting, Gallery of the Louvre, is enjoying greater fame than ever, thanks to David McCullough's new book, The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, which dedicates an entire chapter to Morse's bittersweet ordeal in creating this amazing piece of work.

The story of Morse's creation is told in chapter 3 of McCullough's tour de force of Paris in the 19th century. It's my favorite chapter in the book (or, at least it's tied with chapter 12, which covers Augustus Saint Gaudens creating the statue The Farragut). McCullough uses his chapter on Gallery of the Louvre to provide full background on Morse, his education as an artist, and his journey to become a great painter. If you want the whole story on Morse then I'd highly recommend picking up The Greater Journey. For the purposes of this article, we'll focus specifically on the story of the Gallery of the Louvre.

It was a personal tragedy that brought Morse to Paris to paint his master work. In 1825, his 25 year-old wife Lucretia died unexpectedly just three weeks after giving birth to their third child. A month later, Morse wrote, "My whole soul seemed wrapped up in her. I am almost ready to give up." A year later, Morse's father died and two years after that, his mother passed. With all of these reminders of his mortality staring straight at him, Morse came to one irresistible conclusion. He had to get to Paris to fulfill his potential as an artist. "My education as a painter is incomplete without it," he said.

In November 1829, Morse left his children under the care of family members and sailed for Europe. The 38 year-old American was on a mission to create something meaningful as an artist. Despite the fact that he made his living doing portraits, on his passport Morse listed his profession as "historical painter."

While France was his primary destination, when Morse first arrived in Paris he only stayed for a few months before heading to Italy, where he immersed himself in the Italian classics of art and architecture for over a year. On commission from clients, Morse made copies of many Renaissance works. That's primarily what funded his European trip. Since there was no photography yet and most Americans had never seen the classics, there was a brisk sales in copies -- and lots of bad copies floating around. Thus, some Americans would commission their favorite artists to make copies of specific paintings when they went to Europe. We know that in one case Morse was paid $100 to do a copy of Raphael's School of Athens, a famous fresco in the Vatican.

While in Italy, Morse explored the Vatican galleries and Rome's famous museums and monuments, made tons of notes and sketches, and developed an obsession for the Italian masters. He also met a fellow American, author James Fenimore Cooper, who would become a lifelong friend and a key comrade during the difficult journey Morse was about to take to create the most important painting of his career.

Both Morse and Cooper returned to France in 1831. When Morse arrived in Paris that fall, Cooper told him how impressed he was by the improvement of his work and commissioned him to do a copy of a Rembrandt. However, Morse had larger ambitions in mind. He had a big idea for a new project that could bring an important piece of European culture back to America.

Morse wanted to paint a giant view of the Salon Carré ("Square Room") of the Louvre. Painting whole galleries of famous museums was not completely uncommon at the time and Morse was inspired by The Tribuna of the Uffizi by German painter Johann Zoffany, who did a painting of the inside of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy from 1772 to 1778.

However, Morse would be the first American to do a grand panorama of the inside of the Louvre, and he viewed himself as something of a cultural evangelist, exporting one of the best parts of Europe back to his compatriots.

As if that wasn't ambitious enough, in his painting Morse decided to completely rearrange the artwork hanging on the walls of the Salon Carré. Instead of the contemporary French Romantic works that were hanging there during his time, Morse replaced them with classic European works from throughout the Louvre. He scoured the museum for weeks looking for the best and most important paintings among the 1,250 works that were hung at the Louvre in 1831.

Ultimately, Morse decided on 38 paintings, most of them from Italian Renaissance masters, including Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and Veronese. Because the paintings were hung from floor to ceiling, Morse had to build his own portable scaffolding that he was allowed to bring into the Louvre and move around wherever he needed to get a better view of each specific painting so that he could faithfully render a miniature copy on to his massive 6-foot by 9-foot canvas.

Starting in the fall of 1831, Morse and his scaffolding were at the Louvre seven days a week from open to close to work on the project. As a result, Morse himself became an attraction at the Louvre. Cooper wrote that Morse had "created a sensation." Writing to New York art critic William Dunlap, Cooper stated, "Crowds get round the picture, for Samuel has made a hit in the Louvre."

Cooper became Morse's daily companion throughout the project. Cooper would spend his mornings writing and then in the afternoon he'd walk a mile and half from his Paris residence to the Louvre, crossing the Seine in the process. At the Louvre, he would invariably "find Morse stuck up on a high working stand." By the spring of 1832, Cooper understood how much pressure Morse was under to create a great work and to finish by August 10, when the Louvre would close for the summer. Morse planned to be on his way back to America by September.

Cooper chided Morse, encouraged him, and simply kept him company. Nearly every day after the Louvre closed, the two of them would walk back to Cooper's rented Paris mansion on the Faubourg Saint-Germain and have dinner with Cooper's wife and children and then pass the evening in conversation. Morse lived much more modestly than the Coopers in a small apartment on the Right Bank that he shared with fellow artist Richard Habersham. Other than the time he spent with the Coopers, Morse did almost nothing in Paris other than work on his painting.

In the spring of 1832, as Morse was feeling the pressure of his August deadline looming, a tragedy began to unfold. A cholera epidemic hit Paris. Over 18,000 would die before it passed six months later and many more fled Paris in fear of catching it. Both Morse and the Coopers stayed. On May 6, Morse wrote to his brother, "My anxiety to finish my picture and return drives me, I fear, to too great application... Any one feels, when he lays himself down at night, that he will in all probability be attacked before daybreak." Nevertheless, Morse kept at it day after day, with Cooper there to allay his fears and praise his progress.

Morse focused all his efforts at the Louvre on painting the miniature versions of the works he selected as well as the scenery in the Salon Carré and the Grande Galerie at the back of the room. Morse would save the picture frames and the people in the painting to finish when he returned to New York.

As August closed in, Morse was determined to complete the painting by his deadline and was openly thrilled about how it was coming together. He told his brothers that it was "a splendid work." He even boasted, "I am sure it is the most correct work of its kind ever painted, for everyone says I have caught the style each of the masters."

By the time the Louvre closed on August 10, Morse had completed everything he needed to do on the painting from Paris. And, he'd avoided cholera, which was still killing over 200 people a day. He was ready to put his affairs in order and go home. He hadn't seen his children in almost three years. Around that time, the Coopers left for a trip to Germany and Switzerland. James Cooper asked Morse to wait until the following spring to leave so that they could all travel home together. But, Morse couldn't wait. With the Gallery of Louvre rolled up and safely packed below the decks, he sailed for the U.S. on October 6, 1832.

Back in New York, it took Morse nearly a year to put the finishing touches on Gallery of the Louvre. He wrote to Cooper on August 9, saying, "My picture, c'est fini" (it is finished).

Samuel F. B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre. Click here to view full-screen.

The finished work was remarkable in many aspects. In the 38 paintings Morse chose to spotlight, he proved himself to be an excellent art critic and teacher. He selected some the best classical works that the Louvre had to offer, including a nice diversity of different styles and works whose popularity continues to stand the test of time. He even included Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa -- and this was long before it had achieved international fame as the most popular painting in the world.

Morse also did a fairly respectable job of reproducing the many different styles of the artists that are represented in the 38 paintings -- an impossible task. Over the years, Morse has been criticized for making the people in the various works too cartoonish. There's some validity to that -- especially with the Mona Lisa -- but Morse's painting still succeeds in capturing a little something of the power of almost every work that it portrayed. In nearly every case, it makes you want to know more about each of the works -- exactly what Morse was trying to accomplish.

For me, one of the most appealing things about Gallery of the Louvre is how uncrowded the people are (unlike Tribuna of the Uffizi). Almost certainly, the Salon Carré was rarely ever this empty, with only 10 people in view. This gives me the same feeling as being in a famous building before it opens or being in New York City at 5:00AM and walking through a place like Fifth Avenue, Wall Street, or Central Park. You understand that this place was made to handle a lot more people and you feel a little special that you have it almost all to yourself. Morse's painting has the same feeling. Because there are so few people, it becomes very intimate.

Let's talk about the 10 people who are in the painting. While Morse provided a guide to identify all 38 of the paintings in his work, he never specifically identified the people. Five of them were instantly recognizable at the time. First, is Morse himself standing center stage in the picture, instructing an art student. This is obviously a highly symbolic -- if a bit immodest -- way of showing that the Gallery of the Louvre is not just a painting but an art history lesson taught by Morse. The artist on the far left in the red turban is Morse's Paris roommate Richard Habersham, making a copy of a landscape. The three people in the back left corner are James Fenimore Cooper and his wife Susan, as well as their 20 year-old daughter Sue at work on a copy of a painting.

As for the others in the painting, identifying them is mostly conjecture. The American student that Morse is instructing in the center is generally anonymous, but some art historians believe he modeled her after his daughter Susan Walker Morse. The woman on the right working on a miniature is also an unidentified American, but some have suggested that Morse painted her in the likeness of his widow, Lucretia.

The man entering the Salon Carré from the Grande Galerie at the back is generally thought to be the American sculptor Horatio Greenough, who was a friend of both Cooper and Morse. Fittingly, Greenough is transfixed on the only statue in Morse's arrangement, Diana of the Hunt.

And, last but not least, are the woman and her daughter who are exiting the Salon Carré and heading into the Grande Galerie. The woman is definitely French, since she has a traditional French hat worn in Brittany. Author David McCullough has noted, "She and the child serve as reminders that the museum and its riches are there not for artists and connoisseurs only, but for people of all kinds and ages." It's also significant that six of the ten people in the painting are women. McCullough sees this as Morse's way of encouraging the women of the time in the arts. Morse and Cooper were likely influenced in this regard by their friend Emma Willard, one of the earliest American advocates for the education of women. She was in Paris in 1830.

The final thing I'd like to note about the painting itself is the mood. It glows with a sense of warmth, enthusiasm, and optimism. All of the people in the painting are happy to be there. The Salon Carré looks as if it's bathed in afternoon sunlight. The Grande Galerie in the distance glows even brighter because of its skylights. Morse gave the painting a sense of quietness, softness, and almost a sense of reverence. It's clear that Morse was awed and smitten with the Louvre, and he takes you there and gives you the same feeling -- even if it is just his fantasy of how he wished the Salon Carré could have been arranged.

Once Morse completed the painting in mid-1833, he started preparations to put it on display for the public. There were very few museums in America at the time and for great historical works there was a trend of displaying them individually and charging the public admission to view them. In 1822, Morse had tried this with his massive House of Representatives, which captured the U.S. Congress in action. It was an impressive work, but the exhibition was a dismal failure that didn't make any money. Morse believed the Gallery of the Louvre would be different. It was more exotic. It had the appeal of the Renaissance masters. It was a slice of the best of European culture. He believed it could be a hit, and privately hoped it would bring him fame and fortune (or, at least enough to pay off his debts).

On August 9, 1833, Morse unveiled Gallery of the Louvre in New York City at a popular bookstore called Carvell & Company that had a second floor gallery on the corner of Broadway and Pine Street. Admission was set at 25 cents. Most art critics gave it an excellent review. The New York Mirror wrote, "Here shine in one grand constellation, the brilliant effusions of those great names destined to live as long as the art of painting exists."

Unfortunately, the public was not as enthusiastic. The exhibition didn't even make enough money to break even on the hall rental in New York. In the spring of 1834, Morse gave the exhibit a second chance in New Haven, Connecticut (he was a Yale alum), but the result was the same. The public ignored it.

Distraught, Morse decided to sell the painting. He had hoped that his friend Cooper would buy it, and believed Cooper had hinted at buying it when they were together in Paris. But, Cooper ran into financial difficulties when he returned to the U.S. and wasn't able to make the purchase. A relative of Cooper's, New York landowner George Hyde Clarke, eventually stepped in and agreed to buy it for $1300. Morse had hoped to sell it for $2500.

For Morse, it was the end of his career as a painter. In a letter to Cooper, he wrote, "Painting has been a smiling mistress to many, but she has been cruel to me. I did not abandon her. She abandoned me."

The failure of his masterpiece led Morse to throw all of his energy into his work on the telegraph. He had gotten the idea for it from a communications array he had seen in France for sending signals. However, he soon had several ideas for innovating on the concept by introducing electricity and using a special code for messages (Morse code). By the mid-1840s he was leading the way in a transcontinental communications project that would launch the first stirrings of the digital revolution and forever change the way people view the size of the planet.

As for Morse's Gallery of the Louvre, it remained in Clarke's family until the 1880s and was then transferred to Syracuse University, where it remained for almost a century and even spent a long spell locked away in a basement. The Chicago-based Terra Foundation for American Art bought the painting in 1982 for $3.25 million, which, at the time, was the most ever paid for a work by an American artist.

The painting recently underwent an extensive restoration and is now on loan from the Terra Foundation to The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. until July 8, 2012. It is located in the East Garden Court of the West Building. Admission is free.

One last bit of trivia... Today, the Salon Carré is used exclusively to show off the Louvre's works from the Italian Renaissance. Although the paintings are no longer hung floor-to-ceiling, it's definitely a case of life imitating art.